Posts from January 2012

Nikon D4

I’m one of the few people who shoots video with a Nikon D7000, more-or-less by accident: I bought the thing for stills, and only subsequently discovered that it’s much better for video than its reputation suggests. For the most part its flaws don’t prevent it from capturing lovely images, but it’s sufficiently compromised that one has to take Nikon’s video aspirations with a pinch of salt.

So the Nikon D4 intrigues me, in that if you believe all the blog comments out there it’s become the video DSLR to have within minutes of its launch. It may well be so, but there are plenty of things we don’t know. Chiefly:

- Line skipping, or software downsampling with a low-pass filter? If it’s the former, the D4 is dead in the water for video — as is every other DSLR at this point except the Panasonic GH2 and the Canon 1Dx.

- Exposure metering during Live View/video? There doesn’t seem to be a live histogram, let alone waveform, but hopefully there’s something. If not, we may be able to work around using the zebras in a third-party EVF, but… well, sheesh.

- Aperture control in Live View. Still not clear how this works. Is it stepless? Does it really work?

- 20 minute recording time, apparently. If that’s due to European tax laws, well yah boo sucks and break out the Ninja/NanoFlash/whatever. If it’s instead a heat protection issue — how reliable is the camera for long-form recording via HDMI?

- Audio. There’s clearly hope, but is it really any good?

- Low-light performance in video. The D7000 is excellent, but in video it’s clearly not as good as for stills. How does the D4 fare?

Until we have more information on all of these, it’s wholly premature to assert the D4’s supremacy.

Here’s the thing, though: one of these with a 24-120 ƒ/4 VR would cover a huge range of focal lengths; rigged up it could deliver stunning quality. If everything turns out right it could be right up there with dramatically more expensive cameras like the Sony F3 and Canon C300. And I’d absolutely have one over a Panasonic AF100. Chances are Nikon have bottled or flubbed it. But maybe, just maybe, they haven’t.

So yes, it’s an exciting camera. But please, let’s not declare it a winner until we know more. That’s just noise.

Production models

One of the things we’re doing with the Ri project is setting up production processes from scratch. The whole shebang, from crewing through post-production and delivery, for an in-house production unit and using external freelancers. The key question when doing this is: how much baggage does one carry across from previous production models?

Part of the answer to that rests in another question: how far can you push production values with tiny crews?

Twenty years ago, nobody was expected to be a camera operator, sound recordist, director, researcher and editor, all at once, from the moment they joined the industry. Today, we absolutely expect production staff to be wielding cameras (thank you Sony for the PD150’s legacy) and cutting their own rushes (hat-tip to Apple for Final Cut Pro). But these are (or were) specialist skills, and training and support needs are big variables when you’re setting up a new web channel.

I’ll be blogging here about the process as we learn how to do this, but one thing is already clear: I can’t begin to say how valuable my broadcast experience was. I learned a huge amount from working on big studio shoots, where a 50-strong crew worked seamlessly. Without that background, we couldn’t have done DemoJam, where we threw most — but not quite all — of the studio process away and got away with something much more sustainable. By the skin of our teeth, granted.

But I’m also profoundly grateful that my first real broadcast gig was with a then-tiny team, making Local Heroes for BBC2. The production company, Screenhouse, consisted in those days of myself and the producer/director working from his attic, Adam the presenter in Bristol, a production manager in Harrogate, and another researcher in London, all working from spare rooms, bedrooms, the kitchen table, the sofa, or the local coffee shop. Our fax machines ran hot and our phone bills were huge, but we made transmission.

Nobody told me how ridiculous that setup was; nobody let slip that I was being asked to do impossible things. So I got on and did them.

That, I think, is often the key. Don’t let people know that what they’re doing is impossible. Hire smart people who can learn fast; let them make mistakes; be there to catch them; turn over enough work that you can afford to carry the learning curve.

Bumpy ride? Absolutely. It’s going to be an exciting year.

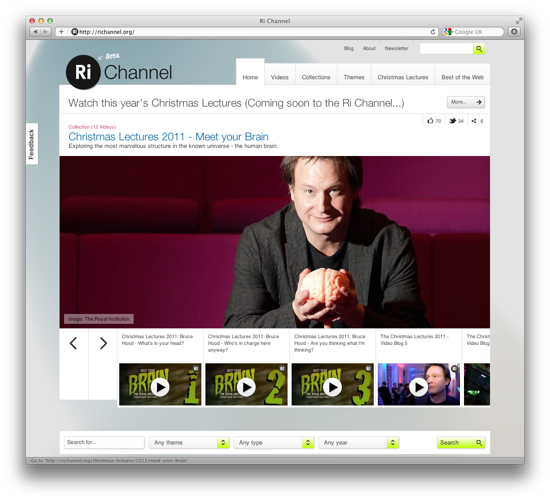

RiChannel

So, this happened:

…which is pretty cool. And which goes some way to explaining why we’ve been so quiet for the last six months. Getting something like this off the ground is, well, busy.

We’ll doubtless have lots more to say about the site, and about what we’re doing behind-the-scenes, but in the meantime — enjoy exploring the site.