Posts from science communication

Pendulums

Over at StoryCog side-project ScienceDemo.org, it’s Pendulum Week! Be sure to visit for your daily dose of swing-based inspiration.

(Yes, we know this is a bit weird. Roll with it, we’re still exploring what we want ScienceDemo.org to be: feedback welcome!)

Craft

Another unapologetically out-of-context quote from Matterson’s article at the BSA:

“Those providing informal learning tend to be driven by their passion and creativity. They evaluate their activities, but the evaluations tend to be locally derived, formative and not linked to research. […] It seems that practitioners can best be characterised as craftspeople, operating through a model of apprenticeship, observation and audience approval. This contrasts with the ‘professional’ tradition whereby formalised mechanisms are developed to record knowledge and train new and existing entrants.”

One of my problems with UK science communication is that it’s managed largely by scientists, who are highly trained to recognise and value only things they can categorise and/or measure.

“There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

Than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

I’m a film-maker. I’m proud to be a craftsman. When behind the lens I delight in the play of light over form; as a director I seduce my presenters into delicate subtlety and nuance, and I obsess over individual edits to a level of finesse my clients will never notice. I’m never satisfied, and it’s always the next film which might reach the standards I set for myself.

My point in the previous post was intended to be: if we aim for science to be a cultural activity, we have to engage with the language and practices of culture. The objectives of cultural activities are rarely ‘learning outcomes’, they’re often far less tangible.

This is why I’ve always been wary of the ‘evaluation is the only true measure of success’ line of thinking. Evaluation is tremendously important and valuable, but it doesn’t capture everything. It doesn’t always tell you if something’s plain shit.

[—edited for clarity, 11/4/2013]

I am not an ‘educator’

One of things I rather like about the UK STEM engagement scene is that we haven’t started using the US phrase “Informal Science Education.” I’ve tremendous respect for education, but the word doesn’t capture all of what I’ve been doing for the last twenty years. So I get a little worried when I read articles like that by Clare Matterson at the BSA site.

Amongst a few sweeping statements (“Those between five and 16 years old are well served”?), these phrases occur in consecutive paragraphs:

“We need a basket of ‘killer facts’ to show that informal learning is not a ‘nice to have’, but a critical component of effective science education.”

&

“Adults are under-served, suggesting that messages about the cultural importance of science to adult society are neglected.”

Hang on: we’ve gone from ‘informal education’ to ‘learning’ to (what appears to be) ‘formal education’, and now to ‘culture’. Which is it?

We’re not going to progress the cultural aspirations of science by using the tools of formal education to measure that progress.

[—edited for clarity 11/4/2013]

Showreel

We’ve (finally) cut a showreel. It features Richard Dawkins, Dava Sobel, Steven Pinker, David Attenborough, Jem Stansfield, Bruce Hood, Alok Jha, Matt Parker, Jon Butterworth… and a lobster.

Showreels, it turns out, are hard. In our case, we’re aware that many potential clients come across our work via some of the more straightforward films we’ve made. It can be tricky to convince them that’s an aesthetic or narrative choice rather than an indicator of our range or inclination, so we wanted a showreel that demonstrated:

- The spread of people with whom we’ve worked.

- Our eye as photographers.

- We’re really good at detailed, close-up, practical science.

- Punchy editing.

- Some serious content.

- …and a sense of whimsy and wit.

Success?

Voice and Tone

“Voice and Tone: Creating Content for Humans at MailChimp” – Kate Kiefer Lee at Confab:

She described part of her job as being “to guard MailChimp’s voice, and keep it consistent across a huge range of content.” She said that the voice stays the same, but the tone changes all the time. Emotions are key to her belief on how important this. The way we write copy on the web affects the way people feel. And, she said, if you get it right, you can “get people to do stuff” — visit websites, buy products, subscribe to services.

via currybetdotnet — Martin is bravely attempting to live-blog the Confab conference, which I’ll confess I only heard of via his blog (RSS: not dead yet, whatever Google thinks).

This is good stuff. I forget, sometimes, that I learned to write primarily by writing for others. Most of the time when you’re writing for speech it’s important to have a voice in your head; when scriptwriting that has to be your character or performer’s voice, not your own. Scriptwriting is an acting job too.

Less obvious, perhaps, is that every organisation should be concerned about its voice and tone. It sounds like Kiefer Lee did a good job of articulating how that can impact the organisation’s bottom line. Read the rest of Martin’s post for some good practical advice.

Another terrific source on this is an interview with Mars Phoenix twitter writer Veronica McGregor, which still ranks as one of the STEM engagement projects I most admire.

Too much information?

Here’s a summary of Dr. No:

The Western world falls under the shadow of a great and mysterious evil. The source of the threat is traced to a monstrous figure, the mad and deformed scientist Dr. No, who lives half across the world in an underground cavern on a remote island. The hero James Bond goes to the armourer who equips him with special weapons. He sets out on a long, hazardous journey to Dr. No’s distant lair, where he finally comes face to face with the monster. They enjoy a series of taunting exchanges, then embark on a titanic struggle. Against such near-supernatural powers, it seems Bond cannot possibly win. But finally, by a superhuman feat, he manages to kill his monstrous opponent. The shadowy threat has been lifted. The Western world has been saved. Bond can return home triumphant.

I’ve chosen that version from The Seven Basic Plots by Christopher Booker, which uses this particular form to illustrate that Dr No shares the same core story as Gilgamesh, written four or five thousand years earlier. Cute.

My point is slightly different, in that you’ve just read a 135-word summary of a 110-minute film. You can comfortably read 135 words, aloud, in under a minute. I just tried, and not just reading but performing that paragraph I clocked myself at 42 seconds. Whatever, the implication is that the running time of Dr No comprises roughly 1% information. What’s the other 99%?

Aesthetics. Emotion. Character.

My hunch is that most fiction fits the same sort of pattern. Where it doesn’t — Game of Thrones, anyone? — we get easily confused, baffled by the number of ideas and suffocating under the proliferation of cast. So, by way of comparison, how do we go about planning science media?

We pack as much information in as possible. In a demonstration lecture we rely on the ‘demonstration’ to drive attention, and shy away from the ‘lecture.’ We run away from aesthetics, emotion and character, which leaves only exposition — and we’re at least dimly aware exposition is the dull bit. Best throw in another explosion.

So we flit from one set-piece to another, relentlessly seeking pace!, excitement!, fun!, inspiration!

Dr. No contains its share of fun, excitement and pace. They’re not without purpose, and we’re not wrong to include them in our work. But our choice to shy away from aesthetics and emotion and character does not always serve us well. We should be good at those things too, and deploy them when they can be effective.

There’s a terrific example to be had in Brian Cox’s recent series Wonders of Life, which took Brian’s trademark emotion and returned an aesthetic sense we’ve not seen in science documentary for some time (if ever, frankly). I’ll have more to say about Wonders of Life in subsequent posts, it’s a fascinating case study. I wasn’t a complete fan.

Graduates in STEM ‘need to rise by half’

The majority of future STEM jobs will be in engineering, requiring almost one in five 21-year-olds to enter the profession between now and 2020

(— via Times Higher Education )

This is reported from a Social Market Foundation report, *In the Balance: The STEM human capital crunch”. The SMF’s own press release leads with the, to my mind, even more explosive:

The Government’s aim to rebalance the economy away from financial services is inconceivable due to a 40,000 per year shortage of home-grown graduates in the science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) sectors

Their argument appears to be based on last year’s RAEng report Jobs and Growth: the importance of engineering skills to the UK economy (link currently goes to a PDF). I haven’t seen much discussion of that report, despite how crucial its conclusions appear to be.

If this is even vaguely correct, those of us working in STEM engagement and education are tackling not a minor, trivial, spare-time sort of problem, but a major national crisis. Surely.

Surely?

The timescale being discussed is ‘by 2020’: people who’d graduate from straight-in 4-year degrees in 2020 have already started their GCSEs. Heck, they’re the generation who might still remember my CITV science shows from when they were 9. You know, before science was removed from children’s TV altogether. And they’re the last year group to fall within this study — everybody for the years before 2020 is already in the pipeline. We can fret about conversion rates, but the ball is already in the roulette wheel and where you place your bet is somewhat irrelevant at this point.

I’ve been meaning to write about this — shout about it — since I first heard of the RAEng report last November. I’m still stunned that nobody seems to be running around screaming that the house is on fire.

I’m particularly baffled that the engineering sector doesn’t appear to see this as a crisis. As their crisis. Why aren’t they frantically looking around the sector, wild-eyed with terror, desperate for anything that might make a difference?

Have they given up? Do they not want to invest? Do they think the Big Bang Fair and Queen Elizabeth Prize have them covered? Perhaps they don’t think this is a tractable problem?

I’m genuinely confused.

The auteur theory of science communication

Prof Steve Haake, producer/director Anna Starkey and camera op/exec. producer Jonathan Sanderson discuss a shot. Photo by camera assistant Ed Prosser while filming Steve’s Engineering Sport series for the Ri Channel.

On his famous seminar Story, the irascible (some might say ‘charmless’) Robert McKee spends a good old chunk of time poo-pooing the whole idea of auteurs in film. They’re defined thus:

auteur n

: a film director who influences their films so much that they rank as their author.

It’s not quite clear from my notes why McKee goes off on such a rant. Probably a Hollywood thing. Or perhaps because it’s French. But it’s a reasonable point anyway, in that the obsessive controlling narcissism shared by directors and writers that everything must be done their way is, for the most part, to be resisted. Even heavily-stylised films like Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive (which I finally watched and loved this week) don’t spring solely from the creative genius of their director.

He had help. Bet you.

Yet, somehow, science communication seems to have latched onto thinking that one individual can do it all. They can present! They can write! They can make the oh-so-critical choice of material! They can market themselves! They can find the relevance to all different kinds of audiences! They can sing! Dance! Fly! Every communicator of science worth their salt can do everything, and their every action is surrounded by magical unicorns!

The perceptive reader will have gathered I’m not a fan of this way of thinking. There’s a basic arrogance to science, I think because it’s so damned hard that everything else must be easier. Right? And to be fair, I do find scriptwriting easier than I found statistical dynamics.

Marginally. Ever so very slightly.

But I think the real reason is a disconnect we have as audiences. When we watch a film we know that the actors are meat puppets — playing a critical rôle, sure, but if the film’s worth watching there are other strong voices in play, those of the director, writer, cinematographer, production designer, and so on.

What’s obvious for movies isn’t always so clear for TV, particularly when the camera is addressed directly. The myth of the author-presenter is so strong that we remember Bronowski, Burke, Attenborough, Johnny Ball. Yet we’ve no idea who worked with them to realise “their” series, nor what their level of creative control was. Brian Cox did not spring fully formed from the loins of Carl Sagan.

He had help. Bet you.

So — communicators of science: work out what you’re good at. Get help with the rest. Not coincidentally, StoryCog can help. Jonathan’s currently working with a former chemistry prof to build his website and marketing message, and just last weekend Alom helped former FameLabbers refocus their performance voice.

We’re really good at this stuff. Some of it. For the rest, we get help.

Three acts

Via Adam Rutherford on Twitter this morning, Billy Wilder’s advice to screenwriters:

- The audience is fickle.

- Grab ‘em by the throat and never let ‘em go.

- Develop a clean line of action for your leading character.

- Know where you’re going.

- The more subtle and elegant you are in hiding your plot points, the better you are as a writer.

- If you have a problem with the third act, the real problem is in the first act.

- A tip from Lubitsch: Let the audience add up two plus two. They’ll love you forever.

- In doing voice-overs, be careful not to describe what the audience already sees. Add to what they’re seeing.

- The event that occurs at the second act curtain triggers the end of the movie.

- The third act must build, build, build in tempo and action until the last event, and then — that’s it. Don’t hang around.

Sounds about right, and applicable far beyond Hollywood screenwriting. Always remember the problems of the three act structure, however: decent rants here and here if you need a refresher.

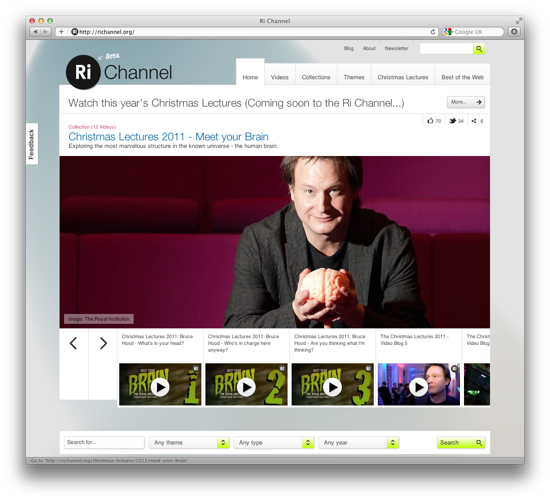

RiChannel

So, this happened:

…which is pretty cool. And which goes some way to explaining why we’ve been so quiet for the last six months. Getting something like this off the ground is, well, busy.

We’ll doubtless have lots more to say about the site, and about what we’re doing behind-the-scenes, but in the meantime — enjoy exploring the site.

Cheltenham, what’s next, and all that

I should probably bang on about the Cheltenham Science Festival, since I’ve finally been. However, in a scant few hours I’m on a train to London, so I’ll have to be brief.

It was fun. It was more fun than I’d expected, which is all the more amazing given that it’s about as over-hyped as I’d expected. There’s lots for a curmudgeon like me to scowl at, but it’s still fun. Well, apart from a certain contretemps between one of my peers and a peer of the realm. More on that another time, perhaps.

I learned stuff, I met some great new people, I caught up with friends old and new. Perhaps best of all, it’s put me in the right frame of mind to tackle StoryCog’s next adventure.

We still have some stuff to sort out and it’s premature to offer any details, but it’s an open secret that it involves the Royal Institution. And you can guess that video is involved. And the web. And, you know, trying to change the world for the better.

That’s what we do.

Meanwhile: there are more of my photos from Andrea Sella’s insane Over-Ambitious Demo Challenge on Flickr. Enjoy.

Excellence in what?

At the Beacons’ Engage2010 conference back in November, one of the more lively sessions involved the stalwart Jim Al-Khalili. He reported on the then-current trains of thought regarding public engagement’s place in the forthcoming Research Excellence Framework, and I think it’s fair to say it was a prickly session. My perception was that many practitioners in the room felt the policy-makers were lagging somewhat.

One specific concern I raised was more strategic: it sounded to me like the sort of system the research councils were considering would tend to reward tried-and-tested, low-risk approaches to engagement. Which is rather in contrast to their approach to research projects, but — if I’m taking a cheap shot here — would put them in step with other funders of public engagement. Ahem.

I haven’t managed to keep up with discussions about the REF, so I don’t know how it’s developing. However, idle chat this morning with Paul McCrory of Think Differently did bring us to another realisation: shifting research councils’ STEM engagement funding into research grants, and assessing that research against public impact metrics, will tend to skew the public engagement audience older.

Suppose you’re a cub researcher, and you’ve been lumbered with delivering your lab’s engagement quota. Or maybe you volunteered, either out of exuberant idealism or because your department head is an inspirational leader (somebody like the aforementioned Al-Khalili, say, or everyone’s favourite chemist Andrea Sella). Whatever, your challenge is to convey your work to a wider audience. More specifically, it’s to increase the public impact of your lab’s research, since that’s what’s being measured by the REF.

The upshot, most likely, is that you do a Café Scientifique slot and a few talks in schools. Great. Both worthy things to do, and unless you’re a really hopeless speaker perhaps even quite effective. For the moment we’ll gloss over whether such approaches are a bit ‘empty-vessel’, because what I’m really trying to get at here is:

When an academic works with a school audience, in most cases they’ll be in a secondary school. Their audience will be 13-18 years old, likely even skewed towards the upper end of that range. Talking about current research with this age bracket is absolutely something we should be doing, and trying our darndest to do really well.

But contrast this with current education research, like the longitudinal ASPIRES project being run by King’s College London. Their starting point goes like this:

There is now considerable evidence that children’s interest in school science declines from the age of ten onwards. The continued under-representation of girls and women in science is also well documented.

Yet research suggests that there is little or no gender distinction in attitudes towards science at age 10, suggesting that there is a critical period between the ages of 10 and 14 in which to engage students.

My question, then, isn’t so much about how the REF is going to promote and develop excellence in engagement work. It’d love to get a solid answer to that sometime, but rather more pressing is:

How is the REF going to increase STEM engagement provision for under-12s?

The research councils would likely say that, frankly, this isn’t their problem. They’re quite likely right.

So whose problem is it?

Make: wave machine

The jelly-baby wave machine film we made last year for the National STEM Centre and the Institute of Physics was featured on the Make: blog a couple of days ago. Yay!

Even before this the film was the most-viewed resource in the National STEM Centre’s eLibrary.

Rubbish

There’s a bunch of stuff I want to write about O2Learn and Jamie’s Dream Teachers, but since we’ve entered the latter I should probably be careful. At least for now.

One thing I did just tweet, however, is this:

Crowd-sourced rubbish is still rubbish. Don’t waste people’s time with it unless you’re offering quality as well.

In this context: don’t waste teachers’ time with crap resources, even if they’ve made them themselves. It’s a waste of a precious resource (ie. teacher time), and you’ll build neither audience nor participation that way.

There are, I think, three alternatives:

- Quality, then scale.

Set a standard, establish a form, then invite contributions. I guess this is what we’re trying with the Physics Demonstration Films. - Nurture, guide, shape.

Your project isn’t about ‘user-generated content’, it’s about investing editorial effort with a wide network of collaborators. Example: compare YouTube, which is full of cats falling in swimming pools and ripped-off TV shows, and Vimeo, which is full of exquisitely-crafted films made by talented directors. I caricature both sites, but you get the point. - Don’t take it too seriously.

Be playful; reward attention by entertaining; keep your utilitarian goal at arm’s length, let people have fun, and trust that where there’s joy there’s value.

I reckon I took all three approaches with SciCast, to varying extents. It’s deliberately silly and playful, and I spent much of the first year of the project on the road running workshops in schools, partly to kick the project off with the ‘right’ sorts of films but also to help judge what kind of support our contributors would need. We’ve done less of the latter than I’d like, but then, we’ve only ever run on a skeleton staff.

All this boils down to one thing: if you’re looking to run a resource site based on contributed content, it’s not about participation and the stuff people give you, it’s about the editorial approach and support you offer to them.